- Home

- Sheila M. Averbuch

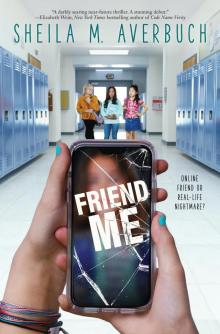

Friend Me Page 7

Friend Me Read online

Page 7

“She inherited millions and spent it all collecting art, building this place—and picking up a few things for herself.” He taps a scrapbook full of newspaper cuttings. “Isabella once went to a dance wearing two huge diamonds on her head, the size of walnuts”—he waggles his fingers over his head—“attached to wires, so they moved like antennae and sparkled in the light.”

Most people laugh, but I get closer to see the cutting: It’s a sketch of Isabella from behind, bare-backed in a gown, giant diamonds bobbing over her head.

“Weirdo.” Zara cuts her eyes at me, and Mara giggles. “Friend of yours? Oh, wait. You don’t have any.”

This time, it’s no stress to look Zara in the face.

“Is that the best you’ve got?” I say, loud enough for everyone to hear. “And who should I be friends with—you? A liar and a fake? No, thanks.”

If I live to be a thousand, I won’t see anything sweeter than the shock on Zara’s face. Her mouth hangs down, like I’m a dog who’s suddenly learned to talk. Like it never occurred to her I might bite.

Two boys bust out laughing. “Burned!” one of them says. Our tour guide shakes his head and waves us on to the next room.

Zara’s cheeks go red, and Mara presses her skinny lips so tight, they vanish. Only half the class follows the tour guide out; the others linger to watch us. The air crackles, like something’s coming. Zara tries to stare me down, but she looks away first, her eyes flicking to the door. She wants to leave, but I’m in the way.

Satisfaction pours through me, like my blood is made of it. Let her see how it feels, having no escape.

Whip-fast, Zara grabs my phone from my jeans pocket. “You want it?” She backs off and holds it behind her. “Say sorry.”

The others oooooh, but I barely hear: There’s a roar in my ears, and something goes pop in my brain. The monster in my chest bursts free, teeth and claws out. I march at Zara.

“GIVE IT,” I spit, and Zara’s smirk wobbles. This close up, it’s obvious how much taller I am.

I lunge for Zara’s arm, but she twists away and is at the balcony in an instant. Someone gasps as Zara dangles my phone over the edge.

My first thought is of Haley: Without her, I’m lost. The splash of the fountain sounds below us. If the fall doesn’t kill my phone, the water will.

I cross to Zara in two steps. Then her hair is in my fist, and I drag her back from the balcony. She wails in pain, and I catch my phone as she drops it, but her cry cuts through me.

I back away, and Zara does the same, swiping her eyes. Loose hairs are caught in the sweat of my fingers. I become aware of whoops and laughter.

“Told you—fighting Irish,” someone says.

My breathing slows. I scrub my hand against my jeans, but Zara’s hairs stay trapped. I feel like I’m going to be sick.

“I lost half my tour!” The guide pops his head back into the room, just in time to see Zara rush to a corner with an ancient EXIT sign, Mara following.

“Not that way, girls!” the tour guide calls. “It’s under construction back there.”

He winces and jogs to where Zara tugs on a door. She mutters that she needs the toilet. The door alarm beep-beeps a high whine. The guide says something into his earpiece, and the sound stops. He presses his palm against a control panel in the wall, and it boops as the alarm resets. He points Zara and Mara to the other doors and a sign for the bathrooms, and herds the rest of us in the same direction.

“No harm done.” He smiles and leads us into a long corridor, making sure we follow this time.

No harm done.

That’s not how I feel. I take out my phone, but my hand shakes too much to tell Haley. What would I say, anyway? “Hey, I hurt Zara! Yay, me!”

My stomach twists. I don’t know how I feel. I can hear whispers hissing around me already, and I’m not even trying: psycho and Irish. I keep my eyes down. My heart still pounds. I can imagine Michael, asking did I make any friends today. No, Michael, I did the complete, absolute opposite. Because that’s me: smoke and ash.

“It is … okay.” For an instant I think the voice is Lily’s, but she’s in the downstairs group with Nikesh. I look up to see Nita, peering at me with what I think is sympathy. I still have no idea why she helped Zara attack me. But I haven’t seen them together since. She tugs out her earbuds and walks with me. “You feel bad?”

I nod. My face must show it: It’s crazy, but I do feel bad for grabbing Zara.

Nita shakes her head and makes a face like something stinks. “She is no good.”

Well, yeah. My arms curl around my middle. Two chairs stand in the corridor where the guide has stopped us to talk about tapestries. I sink down and Nita sits, too.

“So why’d you help her, then?” I glare at Nita. “Why’d you hold me down, in the girls’ bathroom?”

Nita blinks, then looks around. She points to a sign for the ladies’ room: It’s where Mara and Zara have vanished to. “Bathroom?”

I huff. How does she not get this? “No.” I pretend to yank my own arm. “You held me, in the bathroom.” Then I remember the rumors that went around, that I’d tried to fight Zara. My mouth goes dry. “Hang on. Did Zara tell you I was dangerous? That I was going to hurt her?”

Nita’s whole face changes as she suddenly understands. Her eyes drop to her shoes. “Yes. Zara says you are dangerous. Asks me to help. To protect. I believe her. Then, I see what she will do to you, so I leave.” Nita sighs a long breath; this is a huge speech. For the first time I hear her accent, thick and heavy. She shows me her phone. “Sorry. I only speak a little English.”

Now I feel stupid. Nita wasn’t listening to music. On her screen is an app, translating words into English from a language I don’t recognize. “Is that … What is that? It’s not Spanish.”

“Tzotzil. Mayan language. From Guatemala. I don’t speak Spanish.”

“Oh, that’s …” I stare at the portraits, the tapestries—anywhere but at Nita. I think of Lily’s mum, how it never occurred to me that people from Japan could be any race. I had no clue there were people in Guatemala who didn’t speak Spanish. I thought I had it tough, being new to America, but I’m an idiot; being white and speaking English has probably made things a breeze for me, compared to Nita. No wonder she seems a bit of a loner. Even if she spoke Spanish, she’d have things easier: It’s everywhere.

I get this feeling—like I’ve gotten everything and everyone wrong. And I want to make it right. I’m about to ask Nita if she wants to meet up sometime when someone grips my shoulder.

“Volunteers! Thank you.” The tour guide looks stressed. At his side is a girl from our class with a full-on nosebleed, head back and blood on her hands. He finishes saying something into his earpiece and nods at us. “I need two helpers right now. Those selfie girls from your class went to the bathroom but haven’t come back. Fetch them for me, please. I need to stay with this pupil till your teacher gets upstairs.” He taps his earpiece like he’s listening. “Yep, third floor,” he says. “Thank you,” he mouths to us, and turns away, so there’s no arguing.

Brilliant. Fetching Zara is not what I need right now. Or ever. I drag myself off the chair. Nita rolls her eyes and heads back down the corridor to the room with Isabella’s portrait, while I go the other way.

I saw Zara skulk back from the bathroom and have an idea where she might be now. The museum is a series of rooms and wide corridors across four levels, all with windows and balconies overlooking the garden courtyard. Zara and Mara keep doing this stupid thing where they take pictures of each other on balconies, across the open space in the middle. There’s one balcony that’s framed by crazy-long flowers that hang down from upstairs: perfect for a selfie that lets them pretend they’re in an Italian villa.

I spot Zara at the end of the corridor and jog toward her. “The guide says come back. Now!”

She throws me a look. She’s headed for a door that says NO ADMITTANCE, but she tugs it open and sails through, like rules aren’t

for her. “Ooh, you gonna make me?”

I blow out a breath. Anyone else could’ve been sent to fetch her. I’m obviously cursed. I follow Zara into what looks like a gloomy living room. Gilded wood panels glint in the darkness, but most surfaces are draped with sheets, and ladders and toolboxes are dotted about. We’re definitely not supposed to be in here.

I spot Zara and nearly choke. “Are you mad? Get away from those!”

She’s unlatching the glass shutters that cover over the balcony. Some of the balconies have these floor-to-ceiling doors that the tour guide told us to leave alone. Outside, the orange flowers trail down, framing a distant view of our group at the windows opposite. I can see Nita with Mara, who’s holding her phone and waving at Zara to come out and pose.

“Piss off, Roisin. Isn’t that what ye Irish say?”

I pull Zara’s arm, one last attempt to bring her back, but she snatches it away. “Don’t touch me!” she yells, loud enough to wake the dead.

“Fine.” I am done. Let them send someone else to deal with Zara’s mess. Being near her makes me want to scratch my skin off. Sun still lights the courtyard outside. I’m going back for a last look before Zara gets us kicked out.

Zara flings open the glass shutters and steps onto the balcony.

Then time goes strange because it must take just a second, but I see details: the stone dust, the sandpaper, even the kneepads someone left in front of the half-repaired balcony, with its partial railing and the gap that Zara walks straight through—like Michael used to do, when he’d pretend not to see the pool and walk into the deep end, then gasp and splutter in fake shock.

This shock is real, and the screams, too—Zara’s screams—as she twists and grabs at the air, catching only flowers. There are shrieks of “No!” and someone says, “Don’t look,” but we all look at Zara, below us in the courtyard, a crooked shape on the white tiles, the green grass, and a spreading pool of red.

It must have crossed your mind. That she had it coming, I mean.

I shake my head, though Haley can’t see. It was just … so real. If you had seen her. The blood.

I stop typing and rub my eyes. I was dying to tell Haley about the museum, but she’s being … I don’t know. Weird. When our bus finally got back to Eastborough, Mum and Michael were all over me, demanding details. Dad even rang, though it was the middle of the night in Dublin by then. But I couldn’t face going into it with them. I gave them the barest info and slipped away to plug in my phone so I could tell Haley instead: the panic and screaming and how calm the museum people and the paramedics were, making sure we weren’t traumatized by what we’d seen. Mara and Lily both went in the ambulance with Zara. Mr. Morrison was so happy Zara was alive, I think he would’ve agreed to anything.

But she was a monster to u, Ro. I think it’s the universe giving her what she deserved.

I shudder, remembering the impossible angle of Zara’s twisted leg on the ground. One of the huge tree-fern things broke her fall. It saved her life, the paramedics said. She’s super lucky she didn’t smash her head open, I write.

Too bad she didn’t. Drip, drip, dead. Nobody would miss her.

I blink at my phone.

JK, Haley adds, when I don’t reply. Then winky face, crying laughing, love heart.

There’s a soft knock, and my bedroom door opens. A pile of folded laundry, followed by my mother. She frowns at my phone, plucking it out of my hand and powering it off in one smooth movement. “It’s late, sweetheart.” She opens a drawer, puts the laundry inside, and sits on my bed, all of which is so unusual, I know she’s freaked out. I’m too shattered to say she’s the last person who should lecture anyone about being up late. “Do you want to talk about it now?”

I give a groan that I hope will make her give up, but she rests a hand on my leg. She used to do this when I was little: I’d make her leave her hand on my knee or my shoulder till I fell asleep. I roll over and look at her.

“Remember Seamus Dowling?”

Mum nods in the darkness. “Snotty kid.” He was, too. He lived in the farm opposite Granny Doyle’s in Kerry, and he had a permanent wet lip from a nose that streamed constantly. He was always showing off, I think because we were from Dublin. “It was like that time with the fork.” Seamus nearly killed himself and all of us one summer, daring us to jump off things in the barn, till he landed on a pitchfork. He didn’t die, but I’d never seen so much blood.

“Oh, yes. Sorry, darling.” Mum rubs my knee. “The stuff of bad dreams.” She pauses. “That poor girl. I suppose you want to talk it over with the others who saw it, but keep this off.” She puts my phone on the dresser.

I don’t tell Mum that Haley didn’t see the accident; she just wishes she had. I hate that she’s being so brutal about this. Haley’s the only person who knows my whole ugly saga with Zara, including the fact that my brain still wakes me in the night, reliving that instant when she was about to pull up my dress. But then Zara nearly died. So it’s like I’m not allowed to hate her now. Because what would that make me? I need to sort out how I feel. But I don’t think Haley can help.

“Mum.”

“Yes?” she says, when I don’t say anything more. But how can I put it into words?

“The girl who fell—she was horrible. To me.”

“O-kay.” Mum stretches the word, like she’s not sure she wants to hear what’s next. Like I might be about to confess I pushed Zara.

“But I don’t feel glad or yay or anything. Should I?”

“Oh!” I can hear the relief in her voice. Wow. Thanks, Mum. Though, for all she’s seen me in the last few months, I could’ve turned into a murderer and she wouldn’t know. But then Mum sits closer and puts her hand against my cheek, and all I want is for her to keep it there forever. “Darling. Of course you shouldn’t be glad. You’re a human being.”

She kisses my head, which I’m way too old for but which seems okay at two a.m., in the dark. Her cheek leans against my hair, and the smell of her face cream makes my heart well up. I should tell her everything. I used to: updating her on my day, my classes, my friends. But she’s missed too much. And my problems aren’t kid-sized anymore.

She stands up and I realize she’s brought me FRED. She’s holding it under one arm, its black tail drooping down. “Do you want me to …?” She gestures that she can tuck it in with me, if I’d like. I would not like. How can she not know how freaky that thing is? She nods. “Right, then. Get some sleep, sweetheart.”

Sleep doesn’t come. I can see my phone, the black screen reflecting the moonlight. I should switch it on again and say good night to Haley; she’ll think I’m cross with her. After Lily’s party, though, when I went back onto You-chat after Mum said phones off, Jeeves turned me in. He called out a warning, and he must have told Mum, because she thumped the wall between our bedrooms with a muffled but specific threat about taking my phone. I must be the only person in the world whose mother uses robot overlords to enforce her rules.

Wait—not the only person.

I sit up, my insides squirming, remembering Lily. I can still see her, sitting in the ambulance, the knees of her white jeans soaked red where she’d kneeled next to Zara. She and Nikesh were with the tour on the ground floor, and Lily was right there, just after it happened. She yelled into her watch, probably to get her Jeeves to call an ambulance, and peeled off her cardigan to cover Zara. The rest of us froze, as helpful as the marble statue that Zara had missed by centimeters.

I kick off the covers, writing the message to Lily in my head as my phone powers up. If it’s a normal text instead of You-chat, maybe Jeeves won’t tell on me. You were brilliant at the museum, I type super fast. It’s awful about Zara. Talk tomorrow?

I hit send, then hover over the You-chat icon. Maybe I can send Haley a quick message. But my thumb hits the power button instead.

* * *

No one can concentrate on classes today, and by nine thirty our Geometry teacher has put seven phones in jail, a pink cardbo

ard box on his desk. Zara is dead by midmorning, alive again by lunch, and paralyzed by fifth period, according to You-chat, where the comments under Mara’s post—a photo of Zara on a stretcher, being wheeled into Mass General—now have 157 versions of the truth.

You-chat is giving me an utter breakdown, but it’s hard to look away. By last period, people have started asking who was there when Zara fell, did someone push her.

@roisinkdoyle wuz there. I SAW her grab Zara, Mara says.

Irish girl? The one who said she’d rip @zara_xx_oo’s head off?

Y, it was right after she beat Zara down to get her phone back.

I did not beat Zara down! I stopped her from chucking my phone over the balcony!

I try to breathe, but it’s like something is crushing me. This is SO UNFAIR, I could burn the world. It was Zara who bullied me, every day, no mercy. But the instant I reacted, she turned it around, getting me banned from TokTalk, making people think I was unstable.

And now this. The museum. Our fight, then her crazy accident.

At least Lily believes that Zara’s fall wasn’t my fault. Things are, weirdly, good with us. She told me to stay off You-chat, so we’ve been texting. The true story—I heard from Lily—is that Zara shattered her leg and was in surgery all night but should recover. Mara went home, but Lily’s still at the hospital—Mr. Morrison, too. Lily says he’s walking around like a guilt zombie: He says he should’ve stayed with our half of the tour.

No one’s going to blame him, I type. I’m in the loos again, sitting on the shelf by the sinks.

Guess not, Lily answers. The museum shouldn’t have left the balcony half-fixed, or made it so easy for anyone to get into that room. I heard Zara just walked right in there.

I frown, remembering the tour guide. He used his palm print to secure that old exit Zara tried to use. It makes no sense that Zara sailed right through the NO ADMITTANCE door into the room that was under construction. It is weird that we were both able to get into there. The guide said the museum had a huge theft years ago, so the security they use now is super high-tech. But the door wasn’t even locked.

Friend Me

Friend Me